|

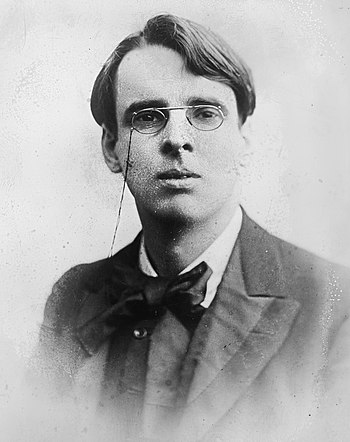

| William Butler Yeats (1865 – 1939), Irish poet and dramatist (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

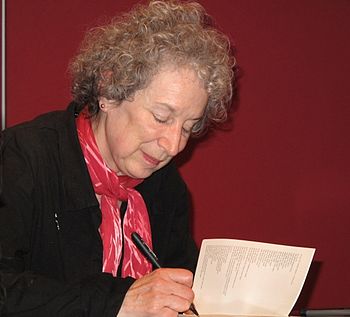

The Nobel Prize laureate WB Yeats was born 150 years ago this June. Poet Nick Laird analyses his unique reading style and describes the challenges of performing verse.

I once read in Dublin with a poet who turned up with what looked like a small wooden suitcase. It turned out to be a sort of buttonless accordion, which, as she read each poem, she slowly opened out to 90 degrees, playing a constant low atonal wheezing throughout. I was surprised – though not as surprised as at a poetry festival in Herefordshire when another contemporary burst into a passionate folk song after she’d read her first piece, a sequence she repeated for the rest of her set. The entire audience – all four of them – went mad for it, though I did subsequently find they comprised her immediate family.

Poets read their poems in all kinds of styles: those who are hunched and intense or relaxed and conversational, or those who hector or lecture their audience, or over-explain or apologise, or crack gags to puncture the slightly tense silence that descends in each poem’s wake. What is now rare is the kind of quavery shamanic intoning – as if summoning demons – practised by WB Yeats, who was born 150 years ago this June.

English poet William Morris rejected the notion of reading his poems as if it were prose

The Irish poet made a series of radio broadcasts for the BBC in the 1930s. He seemed to know even then that his reading manner was going out of style. “I am going to read my poems with great emphasis upon their rhythm, and that may seem strange if you are not used to it,” warned Yeats when introducing the Lake Isle of Innisfree in a 1931 recording. “I remember the great English poet, William Morris, coming in a rage out of some lecture hall where somebody had recited a passage out of his Sigurd the Volsung. ‘It gave me a devil of a lot of trouble,’ said Morris, ‘to get that thing into verse.’ It gave me the devil of a lot of trouble to get into verse the poems that I am going to read, and that is why I will not read them as if they were prose.”

Although all poets – at least all good ones – write in a relationship to rhythm (if not in strict iambs or dactyls or anapaests), techniques now are much more lightly demonstrated. Yeats, though, straddled many periods. He was born in the middle of Victoria’s reign, and his own work began the Celtic Twilight, those soft-focused, eerie lyrics of faeries and gods of the 1880s, but ended with a distinctly clean and modern tone and sensibility with the Last Poems of 1939.

He wrote the Lake Isle of Innisfree in 1888, when he was 23. He was on the Strand in London, he explains, when he heard “a little tinkle of water”, and stopped outside a shop where a ball was balanced on a jet of water – an advertisement for “cooling drinks” – and it set him to thinking of Sligo and lake water.

Just after Yeats was tramping down the Strand, Robert Browning and Alfred, Lord Tennyson made two of the earliest audio recordings of poetry. Tennyson’s, made on a wax cylinder in 1890, has him thundering through the Charge of the Light Brigade. The poem’s short stressed dactylic lines echo the galloping horses, and at some point someone – presumably Tennyson – becomes his own Foley artist and starts a weird knocking sound, trying to imitate the noise of the hooves. Even Tennyson, it seems, was a bit worried that the words weren’t quite enough.

Robert Browning made one of the earliest audio recordings of poetry

Robert Browning’s recording shows a similar fear of dead air, as radio producers now call it. It’s also a classic example of buckling under pressure. In 1889 he was at a dinner party thrown by his friend Rudolf Lehmann, the German artist. A sales manager for Thomas Edison’s Talking Machine, Colonel Gouraud, was also there and had brought along a phonograph. Browning agreed to recite his poem How They Brought The Good News from Ghent to Aix. Again, this is a poem about horses, and his recital has something of the jaunty, excitable tone of a Grand National commentator: “I sprang to the saddle, and Joris, and he; I galloped, Dirck galloped, we galloped all three… ” Then he forgets the lines and does something I think all poets should do if they find themselves in a similar fix: he recites his own name twice, very loudly, and then shouts out: “Hip hip hooray, hip hip hooray, hip hip hooray!”.

For crying out loud

Though both Tennyson and Browning recite their poetry with regard to the rhythm, neither have the singular incantatory oddness of Yeats, of what Heaney has called his “elevated chanting”. We might note that Yeats came to poetry through an oral tradition. He wrote, in the 1906 essay Literature and the Living Voice, that “Irish poetry and Irish stories were made to be spoken or sung, while English literature has all but completely shaped itself in the printing press.” The oral culture in Irish poetry was strong – it is strong – and there is a sense still that the poem should not just be memorable but able to be memorised.

Yeats came from the bardic tradition, in which bards were a professional caste of scholarly, highly trained craftsmen. They attended special colleges for up to seven years to master the technical requirements of syllabic verse that used assonance and half-rhyme and alliteration. The bardic poems were oral history and songs of praise, designed to propel the names of famous kings and the details of their other-worldly deeds down through the ages. The men – and they were all men – were tasked with passing on the accumulated lore of Irish history and legend, and Yeats’s speaking style has something of that eldritch gloom about it: it’s a voice intoning through a banquet hall in candlelight. He wrote, in The Coat, “I made my song a coat, / covered with embroideries / out of old mythologies…”

Although Yeats constantly remade his style throughout his writing life, trimming off the finery of Victoriana, its frills and archaic reversals, to a modern, hard-edged style – what he called “passionate, normal speech” – his formal reading manner remained in the broadcasts he made a few years before his death. And yet it’s true to say that his engagement with the medium was profound. He was at the very beginning of radio culture: the idea of audience for early Yeats was limited to either reciting to a room of faces or communing in silence with a single reader on the page. When he wrote about his radio talks, it’s clear that for Yeats the very technology brought about a new sense of intimacy.

He had previously held off reading more personal poetry. On his American tours, for example, when asked for love poetry, he would respond that he refused to read “any poem of mine which any of you can by any possible chance think an expression of my personal feelings, and certainly I will not read you love poems”. But the radio made possible for Yeats a new kind of conceptual space for reading his more private writing aloud and in public, and in the snug of the studio he was happy to whisper into the ear, as it were, of the audience. “You would all be listening singly or in twos and threes; above all that I myself would be alone, speaking to something that looks like a visiting card on a pole… it would be no worse than publishing love poems in a book.”